Alpaca Stories Part 2: Fibs, Lies, and Falsehood

This article - number two in a series of three was published by Fibershed on March 29 2022. I am grateful for the help of Jaanus Vosu (perualpaca2010@gmail.com ), Walter Antezana, and Mauricio Nunez Oporto.

Image: Ben Ostrower

In my last article: Alpaca – more prized than gold by the Incas, still scorned by the west? we took a very quick look at what alpacas are, why they are so well suited to the Peruvian altiplano, where sustenance is scarce and the indigenous inhabitants have few options, and we price checked alpaca against other fibers – it’s expensive. As discussed in my previous articles on silk, this means that there is an economic incentive for brands and their funded initiatives to portray alpaca as environmentally harmful. Do they? And if so, is it justified?

Let’s start with the MSI, or as it describes itself: “Higg Index, the industry-leading value chain measurement methodology” that is “Trusted across the world” with “ the goal of A common language for collective action.”

This is what the Higg MSI says about alpaca compared to what it says about potential substitutes: acrylic and polyester:

screenshot taken 04/02/2022

As you can see from the screenshot above, the Higg says sourcing alpaca fiber is a very bad idea. Indeed, the MSI ranks alpaca the second most environmentally harmful fabric (after silk), and fashion Brands wishing to use the Higg to minimize their declared impact – whether through the EU PEF, New York State’s proposed fashion act, or their own annual sustainability report – will clearly select acrylic or polyester over alpaca, whenever and wherever possible.

Kering Group’s EP&L, its “tool for the greater good…to encourage a general movement toward greater sustainability”, presents an equally dim view of alpaca:

Screenshot taken 04/02/222ps://kering-group.opendatasoft.com/pages/epl-map

According to Kering almost all of alpaca’s negative environmental impact – €262,000 on a total of €327,000 (80%) – came from ‘Land Use”.

screenshot taken 04/02/2022

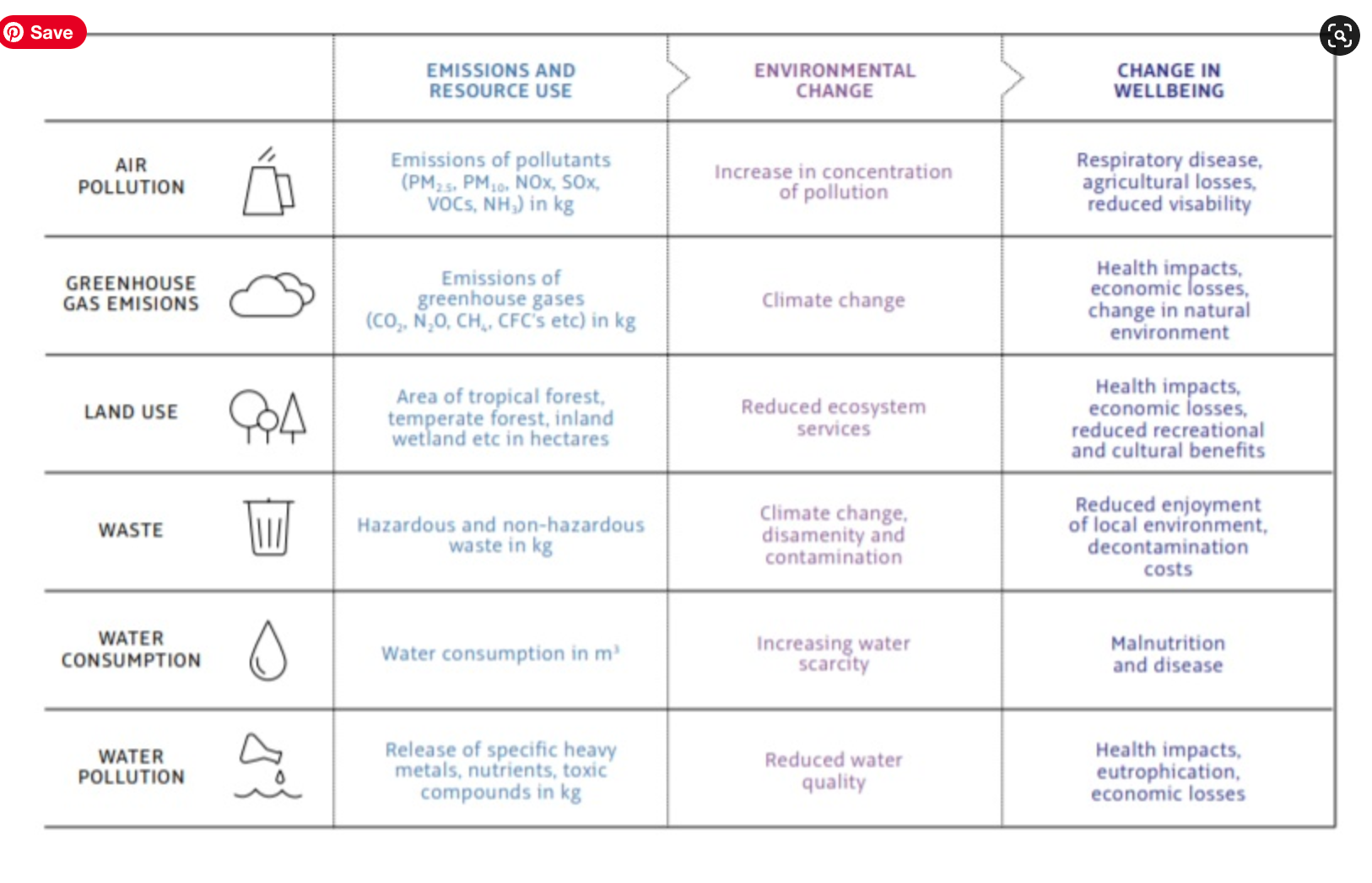

What this means, according to Kering, is that cultivating alpaca in Peru “Estimating the likely environmental changes that result from these emissions or resource use … based on the local environmental context”, results, they have calculated, in “reduced ecosystem services” inducing a negative change in wellbeing through economic losses, reduced recreational and cultural benefits and health impacts.

Presumably because of the purported harm rearing alpaca is doing to the Alpacqueros, Kering has reduced its Alpaca usage, “sum all impacts”, from €801,000 in 2018, to €415,000 in 2019, and €332,000 in 2020.

But is Kering correct? Does alpaca farming reduce “cultural benefits” for the indigenous peoples who raise them?

As far as I can see, the answer to that question is a categorical No. To quote one study (and studies of alpaca farmers are few and far between): “Alpaca farming has a cultural value in Peru. It makes part of the cultural identification of the population of the Andean highlands”, indeed, alpacas are part of indigenous mythology. There are different versions of the sacred origins of alpaca – perhaps they vary with whether you are Quechua, Aymara, or of some other descent – but all the evidence suggests that alpaca were first domesticated roughly 6,000 years ago; that pre columbian herds vastly outnumbered those of today, and that during the Spanish conquest, their population was drastically reduced, partly through ignorance of their value, partly – as with the sheep of the Navajo, under Kit Carson – as a measure to control the local population by destabilizing their means of subsistence. For the indigenous people of the altiplano, to restore the alpaca is to restore their culture, not to harm it.

Nor does farming alpaca reduce the recreational benefits of life in the altiplano. There are countless alpaca photographs in every tourist brochure and on every postcard. Camelid fairs and branding festivals are a feature of local life, and festive ceremonies such as the alpaca Ch’uyay punctuate the indigenous calendar.

Nor is there any evidence that alpaca farming harms the health of the alpaqueros and their families. I have been unable to find a single study blaming the prevalence of alpaca manure for diarrhea or other water borne diseases, nor indeed do toxic chemicals appear to be part of the alpaca cultivation system. It is true that the alpaqueros and their families face serious health problems. These, however, have nothing to do with alpaca farming. On the contrary, the first problem, already mentioned in the context of the death of Óscar Catacora, is the absence of any modern health care facilities in most Peruvian country towns let alone villages. The other problem is mining, about which more later.

Alpaca farming also, categorically does not cause economic losses for the alpaqueros, and it is unclear why Kering would be claiming that it does. Alpaca fiber is the principal cash crop in a region where the agricultural land in many cases cannot even support sheep, where almost the sole viable crop is potatoes, and where transport links are so poor that only a durable, unbreakable harvest, with a relatively low weight to price ratio has any real cash generating potential.

There are two other principal sources of income in the Altiplano – tourism and mining. Alpaca farming clearly does not reduce tourist income – on the contrary it augments it. Indeed, as far as I can discern, the only sector for which alpaca farming represents a potential loss of income, and a negative impact on land access, is mining.

So let’s take a closer look at the Mining Industry in Peru.

image:Pasco Se Defiende

The picture above is of Cerro de Pasco, the 400 year old city, with a population of around 80,000, that is literally being swallowed by a mine. It was once Peru’s second city, based on the wealth of its mines – first silver, then copper. Today the output is zinc and lead, and Cerro de Pasco (CdP) constitutes one of the worst lead-poisoning clusters in the world.To quote the National Geographic “Lead poisoning is a sneaky beast. Even low levels sap energy, make joints ache, and impair learning; moderate levels, especially in children, permanently lower IQs. Go higher and you get convulsions, organ dysfunction, and death.”

Since 2019, the CdP mines belong to a Canadian company Cerro de Pasco Resources Inc. Whether they have done anything to improve the situation, or whether the water of its lakes and rivers still glows orange with mining runoff, and CdP’s citizens still have to buy drinking water from trucks, at 25 times the cost in Lima, is unclear.

The Las Bambas mine, 12,000 feet above sea level, is a more recent operation. It started in 2016. It is owned by China’s MMG Ltd, and it currently accounts for 2% of the global copper supply. To quote a November 2018 report:

“To date, scientific evidence about the impact of the mine has not been published. However, there is a trail of clues. There are malnourished children, sick people, poor schools and shattered health posts, run-down villages without electricity or running water, dead cattle, and thin dirty rivers where trout no longer swim. The people who have lived there for generations feel abandoned by the government and lied to by the mine.”

The realization that in Peru, mining has brought vast wealth for others but little for the local communities who bear the brunt of the negative externalities, is causing increasing hostility to such operations. This has been compounded by previous administrations’ brutal and heavy handed tactics in their attempt to impose mines on unwilling local farmers, who believe they “will ruin our land, and that will be the end of the farming.”

gbreports peru-mining-2021-digital-version

As the map above shows, in 2021 there were 61 main producing mines in Peru. For the indigenous communities that live in the altiplano, it is clearly not alpacas that are causing the destruction of their health, income, recreation, and culture as Kering contends. It is mining.

Moreover, given the recent protests in many indigenous communities and rising dissatisfaction at the failure of mining to bring any benefit to the local population – a dissatisfaction that has been compounded by both the impacts of Covid and the election of left-wing Pedro Castillo to the Peruvian Presidency – we can see a clear incentive for some within the Peruvian administration to portray alpaca farming as the culprit. Here I am reminded of the fate of the Navajo in the 1930s when, as part of Federal Livestock Reduction, their herds of sheep, goats, and horses were slaughtered and their tribal economy decimated. As Richard White observed: “If nothing else demonstrated the political and colonial elements of the Navajo situation, the roots of reduction in the concern over Boulder Dam should… The dam meant nothing to the Navajos; they received no benefits from it. It was a development program geared entirely to the larger society of which the Navajos were a colonial appendage.” The colonizers – mistakenly as it turned out – thought that soil erosion from Navajo land was caused by their livestock. And they worried that it might silt up Lake Mead, rendering the Boulder dam useless for the power generation required by Nevada, Arizona, and most of all (over 50% of the output), by California. So the Navajos’ livestock had to go.

This is particularly worrying as in 2021, according to Transparency International, Peru scored 36/100 on their Corruption Perceptions Index, earning the global rank of 105/180 countries evaluated (Denmark, Finland, and New Zealand were ranked equal first, on 81/100). In 2019, 65% of those Peruvians interviewed thought corruption had increased in the previous 12 months, and 30% of those using public services had paid a bribe in the previous 12 months.

It would be a travesty if those in Peru who profit from and wish to see an expansion in mining activity were to use Textile Exchange’s, Higg Co’s. and Kering’s purported ‘data’ on the environmental harm caused by alpaca farming, to justify the destruction of the herds of recalcitrant Aymara and Quechua farmers, forcing them to relocate. Many would then find themselves in urban slums such as Pamplona Alta. A neighborhood on the wrong side of Lima’s 10 km wide, 3 meter high, barbed wire topped “Wall of Shame” that separates rich ‘gringos’ – so called “by their poor neighbors in a reference to their lighter complexion – tracing back to their European origins”, from their poor, largely indigenous compatriots.

It is interesting to note that Kering’s EP&L includes an impact assessment for copper, including copper sourced from Peru. As you can see from the screenshot below, according to Kering, in direct contrast to every publication that I have been able to find on the topic, Peruvian copper mining has negligible environmental impact. The total impact for 2020 is said to be less than €0.5 per kilo, whilst the negative impact of copper mining in land use, according to Kering, was zero.

screenshot taken 11/03/22

Unfortunately, Kering does not produce a material intensity in € EP&L per Kg of material for alpaca, so we cannot compare like with like. It is however clear that in Kering’s opinion, Peruvian copper mining has no Land Use impact whatsoever. This is an extraordinary claim to make. It flies in the face of all the available evidence, and it is hard to understand what Kering’s motivation in greenwashing Peruvian mining might be. For now, we shall have to leave it there. In my next and final piece in this series, we will take a closer look at claims for alpaca made by the ‘sustainable’ apparel sector.