Alpaca Stories Part 3: When PETA Strikes, Certifications Follow

This article - number three in a series of three was published by Fibershed on March 29 2022.

I am grateful for the help of Jaanus Vosu (perualpaca2010@gmail.com ), Walter Antezana, and Mauricio Nunez Oporto

Image: Alexander Schimmeck, Unsplash. S

The apparel sector stands regularly accused of human rights abuses in its supply chains. As of writing, the Clean Clothes Campaign claims Victoria’s Secret owes US $8.5 million to workers in Thailand, that Nike owe US$1.7 million to workers in Cambodia, and that garment workers globally are owed 11.85 billion USD in unpaid income and severance from March 2020 to March 2021, when many textile corporations used Covid as an excuse to cancel and refuse to pay for goods in process – indeed, in some cases, already delivered. Brands such as H&M committed to introducing a living wage in their supply chains in 2013. As of 2022, nothing has happened.

Not surprisingly then, the major brands and their funded initiatives – particularly the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) and Textile Exchange (TE) – attempt to focus the attention of both legislators and consumers on the purported environmental impact of fibers, whilst keeping the socio economic impact of their sourcing and production choices firmly out of sight and out of mind. The impoverished indigenous producers of alpaca fiber are no exception to this artifice.

In June 2020, PETA released a video of – and I quote: “abuse documented at Mallkini, the world’s largest privately owned alpaca farm, near Muñani, Peru. Mallkini is owned by the Michell Group”

Brands like Marks and Spencer, Esprit ,Valentino, Uniqlo, and the aforementioned Victoria’s Secret, rushed for the moral high ground and committed to “the compassionate decision to ban alpaca”. Not one brand stopped to ask themselves whether, if, as PETA claimed, Mallkini is the world’s largest alpaca farm, their practices accurately represented alpaca production in general, let alone whether the shearers depicted were rogue operators – something found in every industry, everywhere. Indeed Good on You went one better, claiming alpaca: “is often marketed as small-scale and sustainable in the industry. Unfortunately, an investigation into the leading production country of alpaca wool, Peru, has shown the opposite to be true.” Without pausing to notice that PETA had explicitly stated that their findings did not apply to small scale producers but to “the world’s largest privately owned alpaca farm”, or to verify whether most alpaca fiber is in fact sourced from large farms. It isn’t. In reality, some 90% of the supply is estimated to come from smallholders with alpaca herds of less than 100 animals.

Astonishingly, I am told that of the companies targeted by PETA in its alpaca campaign, the sole corporation to actually fact check who was supplying alpaca fiber and how they farmed it, and to fight back, defending the rights of the indigenous alpacqueros, was Hugo Boss.

With depressing predictability, no sooner had PETA published its report than TE announced that it was introducing a ‘Responsible Alpaca Standard”. Peruvian alpaca producers had no choice but to join – or lose their business. As one producer put it:

“the main alpaca guilds, the industry and breeding organizations in Peru have collaborated with Textile Exchange. We see it as a market need for brands to have a certification which will allow them to use alpaca in their collection, and not have PETA on their backs pressing them to drop alpaca from their collections. This is actually what they do, with threats of course, you know how they operate, a money making machine, with little care about the animal welfare at the end.”

But who or what is TE’s responsible alpaca standard responsible to or for? Is it there to maximize the welfare of the poorest on the planet, helping them to improve their health, feed their families, and care for their livestock? Or is it responsible to the brands who need “a certification which will allow them to use Alpaca in their collection.” Because TE certification does not come free. It’s an expensive business.

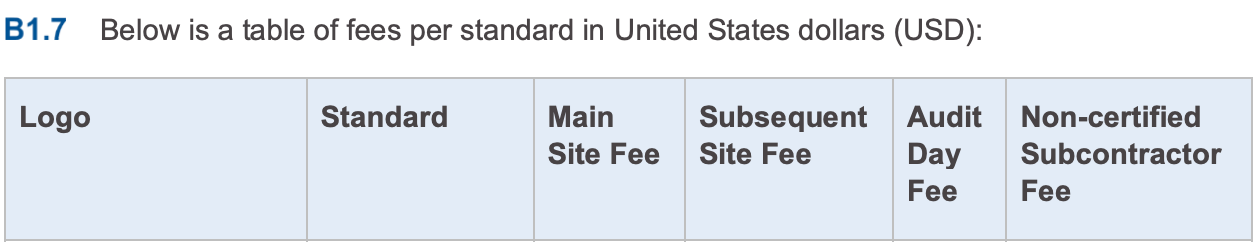

The Textile Exchange Certification Fee Structure 2022, shows the following charges, payable to TE:

With a number of caveats and exceptions, Certification Bodies must pay an application fee of $6000, followed by an annual fee of $2000. They must then pay additional fees depending on the number of sites audited and certified.

I quote:

If a certification body reports more sites than are certified (e.g. through including subcontractors in site counts) and/or more audit days than were performed, the certification body shall pay fees based on the higher total.

Source: Textile Exchange, screenshot taken 16/04/2022

For 2018, the Poverty Line in Peru was US $104.20 per month per habitant. Since INEI estimates that in the main alpaca producing areas as many as 50% fall below the poverty line, it is self-evident that US$200 is more than the entire monthly income of two people – and this has to be paid to Textile Exchange, or the farmer concerned cannot sell his alpaca to our leading brands? Indeed, since the certification body is paying high fees to TE for the pleasure of certifying, presumably the alpaca farmer must pay as much or more again to the agency undertaking the farm audit? The entire monthly income of one family must be paid in “Responsible” alpaca certification fees annually? If correct, this seems extraordinary.

Sources in Peru are under the impression that small farmers will not pay for the certification, it will be a communal certificate, grouping 20-30 farms, and the buyer of the fiber theoretically will be paying for the certification, plus a premium of 7-10% over the market for RAS certified fiber. It remains to be seen whether this works out as promised, or whether alpaca farmers in Peru, like their colleagues producing organic cotton in India, will find that promised premiums do not materialize or fail to cover the additional costs. In any case, whoever technically pays for the certification, it remains the case that alpaca sales proceeds are being diverted away from deprived indigenous producers and into the pockets of Western initiatives.

So do alpaca farmers at least benefit from TE’s exacting standards?

I quote: “Critical requirements are the most important and they shall all be met during the audit to achieve and/or maintain certification. If non-conformity to any of the critical requirements is found, the scope certificate shall be immediately suspended.”

The first critical requirement listed is: “AW1.1 Alpacas shall have access to adequate nutrition, suited to the animals’ age and needs, to maintain normal health and to prevent prolonged hunger or malnutrition.” I have no doubt that most alpacqueros would like their livestock to be as well fed as possible. Apart from anything else, the speed, length and quality of fiber growth, are all directly related to the quality of nutrition. Indeed, Jaanus Vosu informs me that alpaca farmers in Finland are able to obtain finer and more valuable yarn of 16-17 microns (the finest produced in Peru is 18 microns and most is 26), through better nutrition. But to paraphrase Mauricio Nunez Oporto: how can you tell a farmer to pay $30 to buy food for his alpacas when his children are standing there in front of you, and they all have malnutrition?

I quote the World Food Program Peru:

“One of the country’s greatest achievements was the halving of chronic child malnutrition, currently at 13.1 percent. However, rates still vary widely among regions, reaching peaks as high as 33.4 percent in remote rural areas in the Sierra and Amazon regions. Among indigenous people, especially in the Amazon, stunting rates have not decreased in the past ten years.

Almost one quarter of the population (22 percent) still lives below the poverty line and in rural areas deep pockets of food insecurity remain. Limited access to nutritious food is at the root of widespread nutritional problems. These include anemia, which remains pervasive and affects disproportionately the poorest regions and sectors of society.”

Should a “responsible” alpaca standard prioritize the needs of animals over the needs of children? Or should the nutritional needs of the alpaqueros and their families come first?

Image: Federico Scarionati Unsplash

TE’s second critical requirement is “AW1.2 Alpacas shall have an adequate supply of clean, safe drinking water each day.“

Alpaca farmers anywhere near a mining concession – and as we can see from the chart in Alpaca Part 2: Fibs, Lies, and Falsehood, there are a lot of mining concessions in Peru – are, by definition, not going to be able to satisfy this requirement. The farmer cannot supply clean, safe drinking water for his/her family, let alone the family’s livestock.

When dealing with this, shouldn’t a “responsible” alpaca standard include something about TE’s funding brands obligations to their producers, rather than focusing solely and entirely upon the poor producers’ responsibilities to billion dollar brands?

There are a host of other unrealistic requirements in the “Responsible” Alpaca Standard, that the average alpaquero has no hope of satisfying. Why TE chose these is a matter of speculation. Not surprisingly, given the unrealistic hoops alpaca farmers are being made to jump through in order to obtain certification, it would appear that since its launch in April 2021, which was already 10 months after the PETA sting, a mere handful of larger producers/consortiums – such as Michell, the owners of the Mallkini farm that triggered the purported need for a standard in the first place, and Calpex (Consorcio Alpaquero Peru Export) – have only just obtained the certification.

As for PETA and its sting, if large tracts of the Peruvian Andes have no running water, no paved roads, no health centers, no electricity, how can PETA or anyone else claim that electrical shears are the “sound an alpaca sweater makes”? The National Geographic shows us how most Peruvian alpacas are shorn: by hand, often – Jaanus Vosu tells me, in the field itself – with shears.

All of this has the uncomfortable smack of imperialism. It is the interests of the global north that are defining the conversation, and responsibility in the TE’s alpaca standard appears to be to their funders – the major brands – not to the poor in the global south who are producing the fiber.

This western myopia is echoed by SAC Board Members and transparency advisors Good on You (GoY). At the time of the PETA sting, GoY celebrated the destruction of Quechua and Aymara livelihoods:

“even UNIQLO has banned the fibre. While these findings are always shocking and upsetting, it’s powerful to know that people raising their voices against poor treatment can foster change, even in big brands.”

And just this month (March 2022), despite the fact that only 1% of the global population is estimated to be vegan, and even that sector admits that the relapse rate may be high, GoY have had no qualms about asserting:

“Finally, an ethical brand uses no or very few animal products, like wool, leather, fur, angora, down feather, shearling, karakul, and exotic animal skin and hair. Ideally, the brand is 100% vegan.”

So the livelihoods and cultures of an estimated one billion people, predominantly in the global south, are worth less than the shifting preferences of fewer than 80 million in the global North?

Whilst for H&M, being fair means: “exploring ways to replace materials like wool, leather and down with more sustainable alternatives”. And Kering – owners of luxury fashion brands Gucci and Saint Laurent, as well as jewelers Boucheron and Girard-Perregaux, even claims to have lent its know-how to the Responsible Alpaca Standard. But as already noted, this standard appears to impose costs on alpaca farmers without any attempt to improve their livelihoods.

Peruvian alpaca exports totaled a ten-year high of US$219 million in 2018, US$176.4 million in 2019, and only US$120 million in 2020. This collapse in global alpaca sales was matched by Kering’s alpaca purchases. These had a sum all impact of €332,000 in 2020, down from €414,900 in 2019, and €801,200 in 2018.

Clearly, a powerful tool for improvement in both the lives and opportunities of Peru’s indigenous peoples and their livestock, would be a robust and vibrant market for their alpaca.

It is self-evident that, as the untimely death of Oscar Catacora so starkly illustrates, one of the most pressing problems faced by Peruvian Alpaqueros is an almost total lack of access to modern healthcare. It is equally obvious that what would fix that is money – something a thriving industry in alpaca production and processing could provide.

But as we can see from the export data, let alone the prevailing rhetoric, ‘sustainable’ apparel is focused, not on improving sales and earnings for alpaca farmers, but on minimizing costs whilst maximizing greenwashing, for billion dollar brands. And it is the alpaqueros, some of the most disadvantaged people on earth, who are paying the price.

In an interview conducted by La República in September 2018, Oscar Catacora stated that his intention in producing the film Wiñaypacha, was to reassess the Aymara culture. “Say we are here, we exist.”

They are there. If sustainable fashion were sustainable and not greenwash, brands would buy alpaca. But as long as alpaca fiber remains expensive and brands can claim that cheaper plastics like acrylic and polyester are more sustainable, this is never going to happen.